Human trafficking victims are often lured with the promise of jobs. Smuggling a person across a border is a common gateway into human trafficking. The smuggler can become a trafficker by creating a false debt for the “services” of smuggling an individual. That individual is then forced to work to “pay off” the debt.

Modern slavery or human trafficking is a worldwide phenomenon, which cannot be handled by one country alone hence the need for cooperation to eliminate it. Though statistics on the extent of the crime is hard to prove, anecdotal reports suggest that it is increasing. For instance, more than 500 different trafficking flows were detected between 2012 and 2014 across the globe. An estimated 40.3 million people were reported to be in modern slavery in 2017 according to global survey on human trafficking published by International Labour Organization (ILO) and the Walk Free Foundation. In contrast, studies estimate that 4.5 million people around the world are exploited in sex trafficking, including commercial sexual exploitation, pornography, and stripping. While the total annual revenue accruing from human trafficking varies, depending on the source, but it is estimated to be between US$ 5 and US$42 billion.

Human trafficking happens to the most vulnerable people, meanwhile, a new report by the UN drug and crimes agency warns that the Covid-19 pandemic could also be contributing to a rise in trafficking of persons. The Trafficking in Persons Report says poverty arising from lost jobs or other economic opportunities has, over the last one year, increased the pool of people most vulnerable to being trafficked.

It has been estimated that 3.7 million people in Africa are in slavery and forced labour at any given time, and the annual profits generated from these amount to $13.1 billion in this region alone. Many traffickers are known to the victims and include close family members, relatives and friends. Interestingly, 50% of these traffickers in Africa are female, dispelling a myth that it is a male-dominated crime. The involvement of sophisticated organized criminal groups has also been recognized, and this makes the trafficking operation more sophisticated and dangerous.

Lesotho is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy in Southern Africa. In recent years, the army’s involvement in the country’s already fragile politics has resulted in political instability and a security crisis. A total of six people have served as Prime Minister of Lesotho (not counting one Acting Prime Ministers and two Chairmen of the Military Council). Additionally, three persons, Ntsu Mokhehle, Pakalitha Mosisili and Tom Thabane, have served on two non-consecutive occasions. In May 2012, Prime Minister Motsoahae Thomas Thabane replaced the 14-year incumbent, Pakalitha Mosisili, in the country’s first coalition government. Mosisili returned to power in 2015. The current Prime Minister is Moeketsi Majoro, who was sworn in on 20 May 2020 after the resignation of Tom Thabane. Human rights groups note a high level of political instability. Corruption remains a challenge. Customary practice and law restrict women’s rights in areas such as property, inheritance, and marriage and divorce.

The World Bank classified Lesotho as a low-income country. Lesotho mostly depends on an economic base of textile manufacturing, agriculture, remittances, and regional customs revenue. The country exported USD 367.3 million worth of textiles in 2012. The Government of Lesotho is the country’s largest employer, and government consumption contributed to 37 percent of GDP in 2014. The largest private employer is the textile and garment industry where approximately 40,000 women work in factories producing for export.

[h5p id=”686″]

In recent years, Lesotho’s economic performance has been negatively affected by sluggish global economic growth amid a major downturn in both emerging markets and advanced economies. Sustained political instability in the country, coupled with slow economic growth in the South African economy, also contributed to slow economic performance. GDP growth decreased from 3.5 percent in 2014 to 1.7 percent in 2015. The decline was mainly attributed to lower growth in South Africa, lower global growth prospects and the drought.

[h5p id=”687″]

Diamond mining has grown in recent years and accounted for more than eight percent of GDP in 2015. Lesotho’s economy grew at an estimated 2.6% in 2019, up from 1.2% in 2018 owing to strong mining performance and a textiles recovery in an improved global economy, according to African Economic Outlook (AEO) 2020 of the African Development Bank (AfDB). Similarly, the World Bank report noted that Real GDP growth rate is estimated to have averaged 1.6% between 2015–2019 and it is projected to average 0.6% between 2019–2021, largely attributed to the expected negative impact of COVID-19 (coronavirus).

[h5p id=”688″]

Unemployment remains high at 23.6% in 2018 coupled with high inequality and poverty. The national poverty rate declined from 56.6% in 2002 to 49.7% in 2017. Urban areas registered strong poverty reduction of 13 percentage points, while rural areas poverty rates levels decreased marginally by 0.6 percentage points, leading to wider urban-rural inequality.

[h5p id=”689″]

Over the same period, extreme poverty declined from 34.1 to 24.1% while the poverty gap declined from 29.0% to 21.9% leading to a lower Gini coefficient, hence the narrowing in the income inequality in the country. As such, Lesotho is more equal than its neighbours, with a Gini coefficient of 44.6. However, it remains one of the 20% most unequal countries in the world.

[h5p id=”690″]

Lesotho is a small country with a population of two million people, 99.7 percent of whom are part of the Sotho ethnic group. More than half of Lesotho’s people live below the poverty line and the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is the second highest in the world. Between 1990 and 2005, life expectancy at birth declined from almost 60 years to 47 years. HIV incidence is still high at 1.9 new infections per 100 person-years of exposure. The on-going healthcare crisis in Lesotho’s public health care system primarily is a result of healthcare debts according to Amnesty International.

Meanwhile, the number of mineworkers has declined steadily over the past several years, a small manufacturing base has developed based on farm products that support the milling, canning, leather, and jute industries, as well as a rapidly expanding apparel-assembly sector. The Human Development Index (HDI) in 2018, shows that the average human development score in Lesotho is 0.518. This score indicates that human development is low. The economy is still primarily based on subsistence agriculture, especially livestock, although drought has decreased agricultural activity. The extreme inequality in the distribution of income remains a major drawback.

Lesotho’s economy is significantly open to global trade. As COVID-19 is expected to impact supply chains, thus hampering trade, as most textiles and apparel firms in Lesotho source raw materials from China, which is the epicenter of the COVID-19. Similarly, commodity exports to major economies such as Euro Area and the United States are most likely to be negatively affected. The tourism sector is also expected to be negatively affected by the advent of COVID-19.

Lesotho has become less reliant on South Africa for electrical power as of late, but concerns exist regarding how the extended Eskom crisis will affect the country. Poor infrastructure and distribution issues plague the country’s water supply and have put high demands on this resource. The water supply in Maseru has been largely uninterrupted, but the water system has been less reliable outside of the capital, leaving even medical facilities without water and in drought-like conditions.

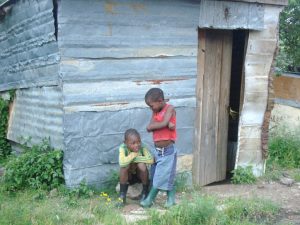

Child sex trafficking is a growing problem around the world. In Lesotho, children engage in the worst forms of child labour, including commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also perform dangerous tasks related to animal herding and domestic work. Lesotho’s compulsory education age is below the minimum age for work, leaving children in between these ages vulnerable to child labour. The government also lacks sufficient mechanisms to combat child labour, and labour inspections are not conducted in high-risk sectors, including the informal sector.

The main actors involved in this crime are the trafficked persons, the traffickers and the users of trafficked victims. These people end up being part of the human trafficking chain because of various reasons that are either push or pull factors. Pull factors might include a demand for domestic and sexual services or economic differentials that make even relatively poor neighboring cities, regions or countries seem a likely source of livelihood. Push factors mainly include poverty, gender discrimination, lack of information and education, HIV and AIDS, violence against women, harmful sociocultural practices and lack of legislative and policy frameworks.

South Africa has been identified as both a key destination as well as a country of origin and transit for individuals trafficked to and from Africa and globally. Awareness of trafficking is increasing within South Africa, and with it the impression that levels of trafficking have reached alarming proportions – with one recent media report arguing that upwards of 600,000 people are trafficked through South Africa every year. Human trafficking is on the rise as promises of jobs continue to lure Basotho citizens into South Africa. In 2019, media report disclose that South Africa’s scrap laws that required travelers to produce unabridged birth certificates and supporting documents for children travelling across its borders has left Basotho minors prone to human trafficking.

Trafficking into South Africa is particularly easy. Some of the borders are open for 24 hours or late into the night, and border control is very slack. Lesotho provides the quickest route into South Africa for traffickers because once one has crossed the border, the nearest South African town is no more than a few kilometers away.

Traffickers often recruit male and female street children, victims of physical and sexual abuse at home, or children orphaned by AIDS. Such children normally migrate from rural areas and border towns to Maseru, the capital, from where they are trafficked by mostly South African white Afrikaans to work in farms in Eastern Cape.

The closure of textile factories has left a lot of female workers without any work. This economic reality makes them particularly vulnerable to traffickers. Long-distance truck drivers offer to transport women and girls looking for legitimate employment in South Africa. En route, some of these women and girls are raped by the truck drivers, then later prostituted by the driver or an associate. Many men who migrate voluntarily to South Africa to work illegally in agriculture and mining become victims of labour trafficking. Victims work for weeks or months for no pay; just before their promised “pay day” the employers turn them over to authorities to be deported for immigration violations.

Women and children are exploited in South Africa in involuntary domestic servitude and commercial sex, and some girls may still be brought to South Africa for forced marriages in remote villages. Some Basotho women who voluntarily migrate to South Africa seeking work in domestic service become victims of traffickers, who detain them in prison-like conditions and force them to engage in prostitution.

Lesotho has no comprehensive anti-trafficking law, although its Constitution prohibits slavery, servitude, and forced labour; Article 15. ( Right to protection from exploitative labour) states that: “A child has a right to be protected from exploitative labour as provided for under section 226 of this Act and other international instruments on child labour.” Recently, a leading local watchdog, Transformation Resource Centre (TRC), slammed the government of paying lip service to the US government’s concerns. TRC it said in a statement that, the authorities lack of seriousness in addressing the issue could affect human rights of Basotho and lead to the loss of economic opportunities which the southern African country had gained over the years from US development assistance programmes such as the multi-million-dollar Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC).

However, Lesotho’s Minister of Home Affairs, Motlalentoa Letsosa, noted in a report that Lesotho has submitted its report to the U.S. government detailing the measures it has taken to address the latter’s concerns about alleged rampant human trafficking. Moreover, Motlalentoa has refused to say whether they had begun investigating and prosecuting high profile people including senior government officials, as was demanded by the U.S, report stated. This puts the country on the brink, with the real risk of losing billions of maloti in funding under the second compact and about 45 000 textiles jobs facing serious jeopardy.

Consequently, government made a moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labour in 2019. Lesotho ratified ILO Protocol 29 to the Forced Labor Convention of 1930 and published data relevant to child labor from the UNICEF-supported Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey and the Violence Against Children Survey. Despite government efforts, Lesotho continues to face diverse and complex challenges in the protection of Victims of Trafficking (VoT) as well as in tackling the issues of trafficking in persons and smuggling of migrants.

- High poverty rate

Women are vulnerable to trafficking because they have less access to employment, resources and other means of earning a livelihood. Studies indicate that, the unemployment rate for women is particularly high – up to 70%. It is critical that development policies are targeted at poverty alleviation.

- Poor education system

Lack of access to education and means of livelihood expose children to situations of trafficking. Low education levels and illiteracy reduce employment options for workers and often force them to accept work under poor conditions. There is a lack of information and knowledge about trafficking because of the silence surrounding the problem. For instance, individuals who can read contracts may be in a better position to recognize situations that could lead to exploitation and coercion.

- Experts believed that, increase efforts to investigate, prosecute, and convict traffickers through independent and fair trials, including officials complicit in trafficking crimes.

- Finalize and implement guidelines for proactive victim identification and standard operating procedures for referring identified victims to care, in line with the anti-trafficking act regulations.

- Adequately fund the Child and Gender Protection Unit (CGPU), and establish a CGPU focal point in all 10 districts of Lesotho to ensure effective responsiveness to all potential trafficking cases.

- Adequately fund shelter and protective services for victims.

- Provide trafficking-specific training to police investigators, prosecutors, judges, and social service personnel. If policy makers, law enforcers and communities are aware of the existence and evils of human trafficking, it will be easier to identify, prosecute and punish all actors in human trafficking.

- Amend the anti-trafficking law to remove sentencing provisions that allow fines in lieu of imprisonment and remove the requirement of force, fraud, or coercion to constitute a child sex trafficking offense.

- Public acknowledgement and creation of awareness of the problem would contribute significantly towards its eradication. Especially among populations most at risk, such as schoolchildren, undocumented migrants and young women on the transit routes from rural areas to the cities.

- Allocate funds for the Victims of Trafficking Trust Fund and implement procedures for administering the funds.

- Allocate funding to support operation of the multi-agency anti-trafficking task force. Achieving SDG Target 8.7 will require national governments to take direct action against the forms of exploitation through policy implementation.

- Legislative, political and economic measures must be undertaken at national, regional and international levels to eradicate human trafficking. Amend the anti-trafficking and child welfare laws so that force, fraud, or coercion are not required for cases involving children younger than age of 18 to be considered trafficking crimes.

- Fix jurisdictional issues that prevent magistrate courts from issuing the maximum penalty for trafficking crimes.

- Increase efforts to systematically collect and analyze anti-trafficking law enforcement and victim protection data.

- Increase oversight of labour recruitment agencies licensed in Lesotho to mitigate fraudulent recruitment for mining work in South Africa.

- Improve the numbers, staffing and security of rehabilitation facilities for dealing with the complex trauma as a consequence of victimhood would also be welcomed.

Be First to Comment